Recently I was teaching a World Literature course and we were discussing Bakhtin’s concepts of signs and utterances. A student began to make the argument that tone of voice and body language could allow a communicator to reduce the utterance “I love ice cream” down to just “ice cream” if the appropriate body language accompanied to express love for it. My response was yes, that’s true, but body language and tone of voice are not signs, because we don’t have consistent agreement on those signs. A shrug may mean one thing to you and another to someone else. As someone who works in Discourse Analysis, in the back of mind I am cringing at that answer. I stand by it, but it was one of the shortcomings of Bakhtin as he was never concerned with visual rhetoric.

We have all gotten a song stuck in our heads before, and usually it’s a song we don’t like or will grow to hate from having it rolling around in our noggins all day. My spouse taught me that those are called “earworms.” For me it’s always pop music that I can’t stand, like getting a Backstreet Boys or Chumbawamba song whose chorus repeats over and over until your insane in the brain. I mention this only because it is the perfect example of what we might call an infectious meme.

I would like to take a look at the infectious nature of visual memes in the adaptation process of several Frankenstein productions and various derivations. While I know pictures of Frankenstein’s Monster existed before the age of film, I am basing most of this on the argument that Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is the major influence on James Whale’s Universal film, Frankenstein (1931), and that James Whale’s take on the creature, and later his bride, is what serves as precedence for the character from that point on.

A meme is the smallest unit of cultural meaning, similar to Bakhtin’s utterance as the smallest unit of communicative meaning. In a previous post, I spoke of Susan Blackmore’s concept of the selfplex and memeplex in the bio-evolutionary model of adaptation. Essentially a meme is the multi-media version of Bakhtin’s utterance, and they spread through society by leaping from the memeplex, a sort of cultural pool, into our minds or selfplex. My argument is that this is similar to the way viruses spread and the evolution of the meme is something we can track like an epidemiologist.

Thinking about a meme as a virus can help us understand how infectious memes can be. Like the earworm song, images get stuck in our heads and often never leave. Those memes take up residency in our memories and basically influence all the intertextuality and intersubjectivity that comprises our id and super-ego. I tell my students we all view the world through our own cultural lens because of the baggage we carry. In this case, those iconic Dore images are an inescapable influence on an artist’s rendition of the characters. Dore’s memes have infected our minds to the point that we can never be inoculated against it. Just like that time you walked in on your parents in flagrante in the act of coitus, you can’t un-see it. Try to read a Thomas Harris’ novel and not picture Sir Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter.

Which brings us to our favorite Romantic offering of the greatest feminist treatise in the history of “man”, Frankenstein. Mary Shelly’s masterpiece, as we all know, never mentions the methods by which Victor brings the creature to life. All we know is that he studied alchemists from the eras of Scientia, that time period between magic and science. The concept of electrodes and theremins are all modern inventions that occurred after the novel’s initial publication. I have always been interested in why adapters feel the need to focus on the “science” of creating the monster. There is always some attempt to base it in hard science. In James Whale’s version, we get the introduction of what becomes classic visual iconography for the film. From 1931 on, the monster often tends to look similar to Boris Karloff and the famous flat-top, and of course we can’t imagine his creation without the bubbling beakers and explosions of electricity. While I would argue that Whale is essentially creating a “big bang” spectacle of the creation of life, he is also channeling his inner man-crush on Fritz Lang in doing so.

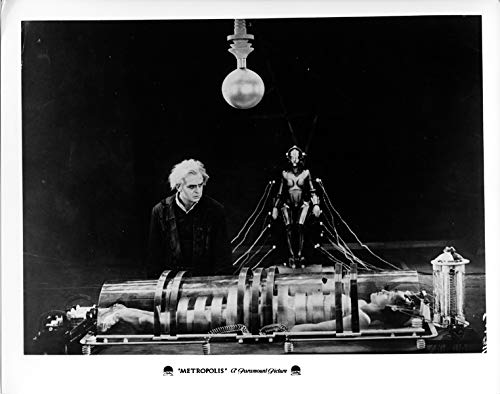

Whale is known to have been heavily influenced by German expressionist filmmakers, in particular the works of Fritz Lang (Metropolis 1927) and Robert Weine (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari 1921). While we see a lot of Lang’s influence in Frankenstein (1931), it’s really in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) that we really see the iconography truly emerge. To begin with, though, let’s consider the operating table or slab that the monster is usually strapped to during the creation process. While all the beakers and electro-balls are definitely visually appealing and stick with us, I would argue it is actually the image of the monster strapped to the slab that is what becomes the iconographic meme.

The creature-on-the-slab theme is something that gets repeated a lot in future adaptations of Frankenstein, but also those stories and productions using and/or paying tribute to the original story. Consider the end of Star Wars III: Revenge of the Sith when (spoiler alert) Anakin Skywalker falls into the lava. This is essentially what turns him into one of the most iconic villains of the modern era, Darth Vader. The film’s ending features a shot of the newly suited Vader, strapped to a “space-gurney” in a direct homage to Whale’s creature-on-the-slab.

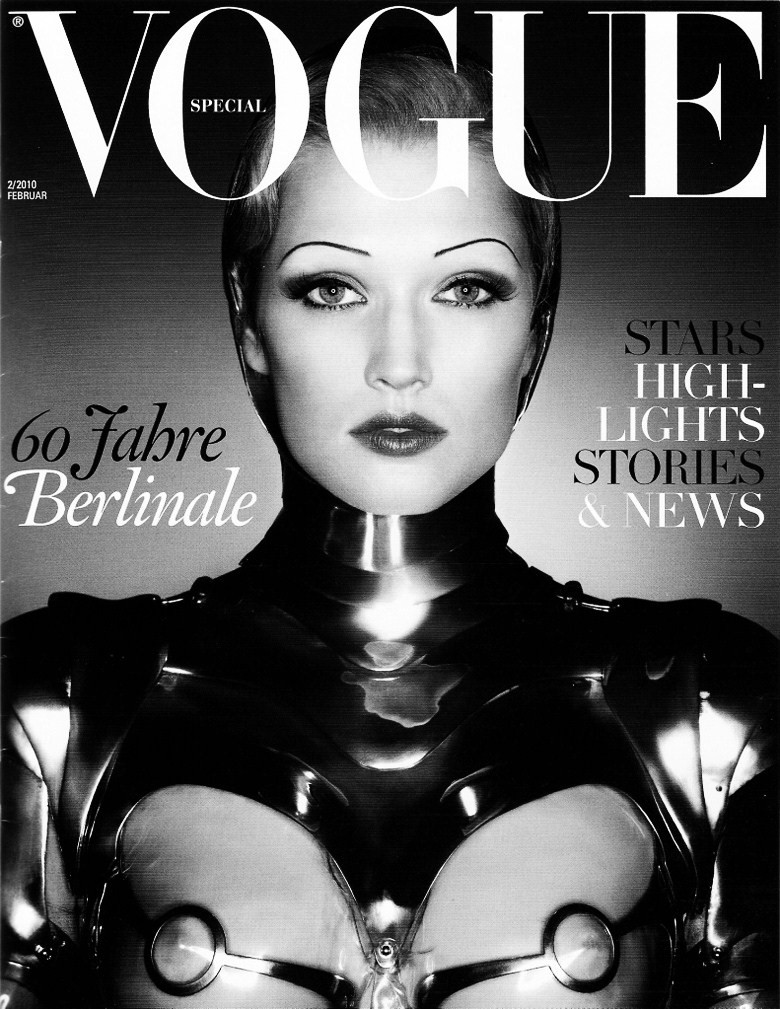

Where I think Lang’s influence on Whale is really obvious is in the sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Here we see homages in the reproductions of scenes from Metropolis (1927). Once again we see the introduction of “electro elements” and automation of either woman or machine, or both if you delve deep enough.